Posted on 30 November 2021 by Jeff Fuge | Reading time 3 mins

Legendary designer, illustrator, writer, teacher – and one of my heroes – Bob Gill passed away on 9 November, aged 90. Bob co-founded Fletcher Forbes Gill back in the ’60s, which grew to become the internationally respected agency Pentagram.

Little guy, massive influence

I was lucky enough to attend a talk by Bob in London in the late ’90s. He spoke with a proper ‘Noo Yawk’ accent and enjoyed telling it like it is, and being a huge supporter of my profession by – in part – being tough on its weaknesses.

Some speakers at design conferences are all inspirational carrot, wowing you with what they’ve done. I’d say Bob was 50-50 carrot and stick: here’s why the stuff we do is difficult, here’s how you’ll make a mess of it… but here’s how to shine.

Memories play a few tricks, but I recall Bob being a little guy. A little guy whose thoughts, ideas, humour, experiences and attitude filled the room.

At the heart of Bob’s philosophy was the idea that us designers are facing an ever-increasing challenge. Everywhere, people’s heads are being turned by the big-budget special effects of Hollywood movies.

(Remember, this was the ’90’s. I suspect he would have added the equally blockbuster worlds of computer games and equally distracting influence of social media and mobile apps today.)

“How can a graphic designer compete with this magic?” he asked. “We don’t have the technology or the budgets, or the time.”

“If we want to attract attention to our work we must take a look at the real world and say to our audience, ‘Look! Have you ever noticed this before? Even though it was right under your nose?’”.

To Bob, seeking out that seemingly simple but bloody-difficult-to-find idea or observation in relation to the client’s brief was the cornerstone of being a good designer.

I couldn’t agree more.

Unspecial effects, very special advice

In his brilliant 2001 book Unspecial Effects for Graphic Designers, Bob makes a point that has become even more pertinent as time has gone on. He says that for under $100 you can buy a computer programme that fit words and images into professional-looking formats. This allows anyone with basic typing skills to produce most of the design and print materials needed by an average business.

Twenty years later, and software and services such as Canva and Designs.AI are ramping the volume on that statement up to 11.

So, says Bob, if a typist can do much of the work previously done by specialists, what’s left for the designer?

We have to do things someone armed solely with some slick software can’t do… we have to think, observe and go beyond what ‘the culture mafia’ feeds us. We have to avoid regurgitating what’s hot, what others coo over and think cool, and find something interesting “or event better, something original” to say.

And only when you’re satisfied with what you want to say can the design process begin.

Bob implores us try to forget what good design is supposed to look like and listen to what he calls the ‘statement’. (The statement is that interesting or original thought you uncovered through painstaking and passionate immersion in the subject at hand). “The statement will tell you what it should look like. It will then design itself. Well, almost.”

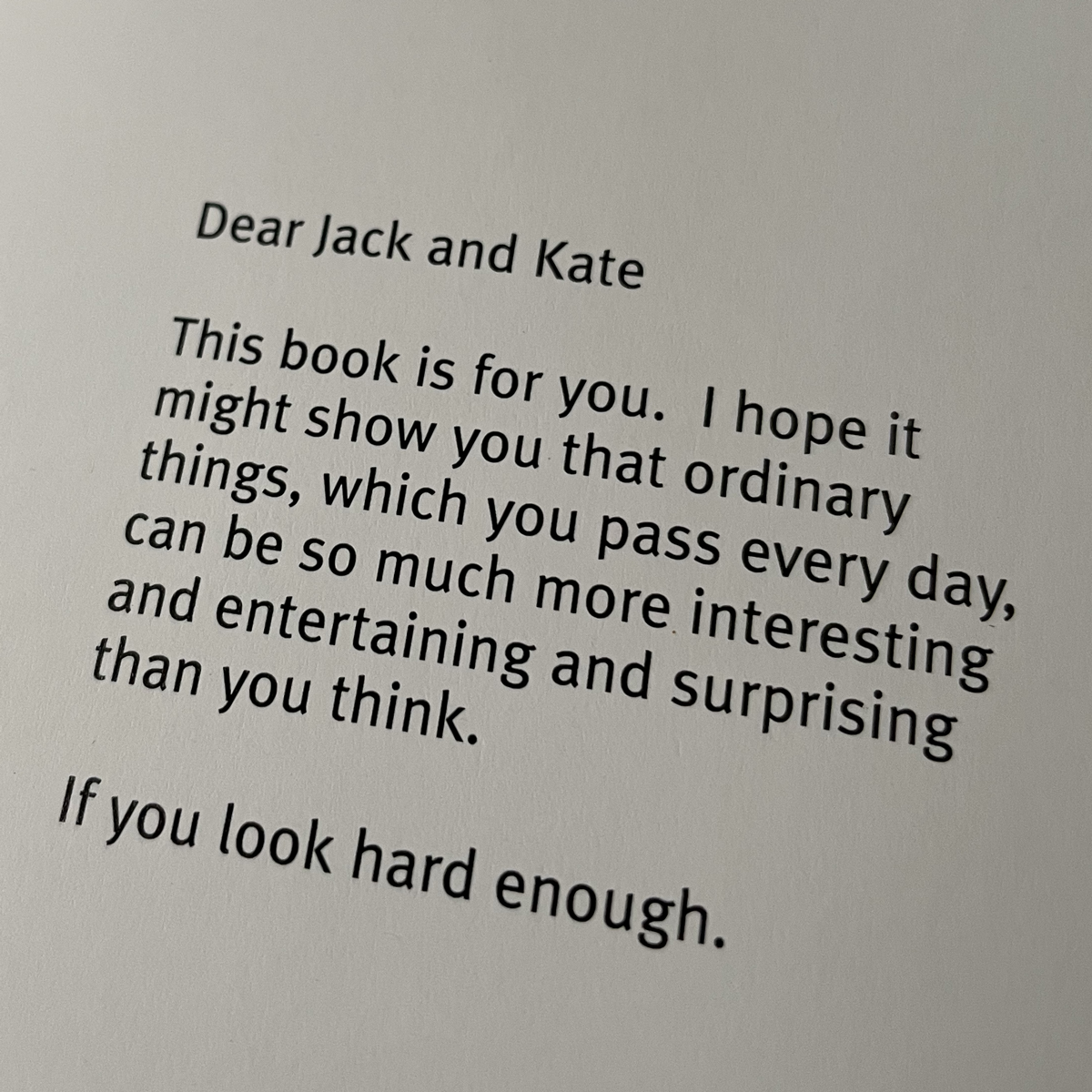

Bob dedicated Unspecial Effects to his children, Jack and Kate. He writes that he hopes it might “show you that ordinary things, which you pass every day, can be so much more interesting and entertaining and surprising that you think. If you look hard enough.”

We’re in a time when people spend so much time looking down at screens not around at real-life scenes. So, we could all benefit by accepting this invitation to look up and discover the amazing things we’re missing.

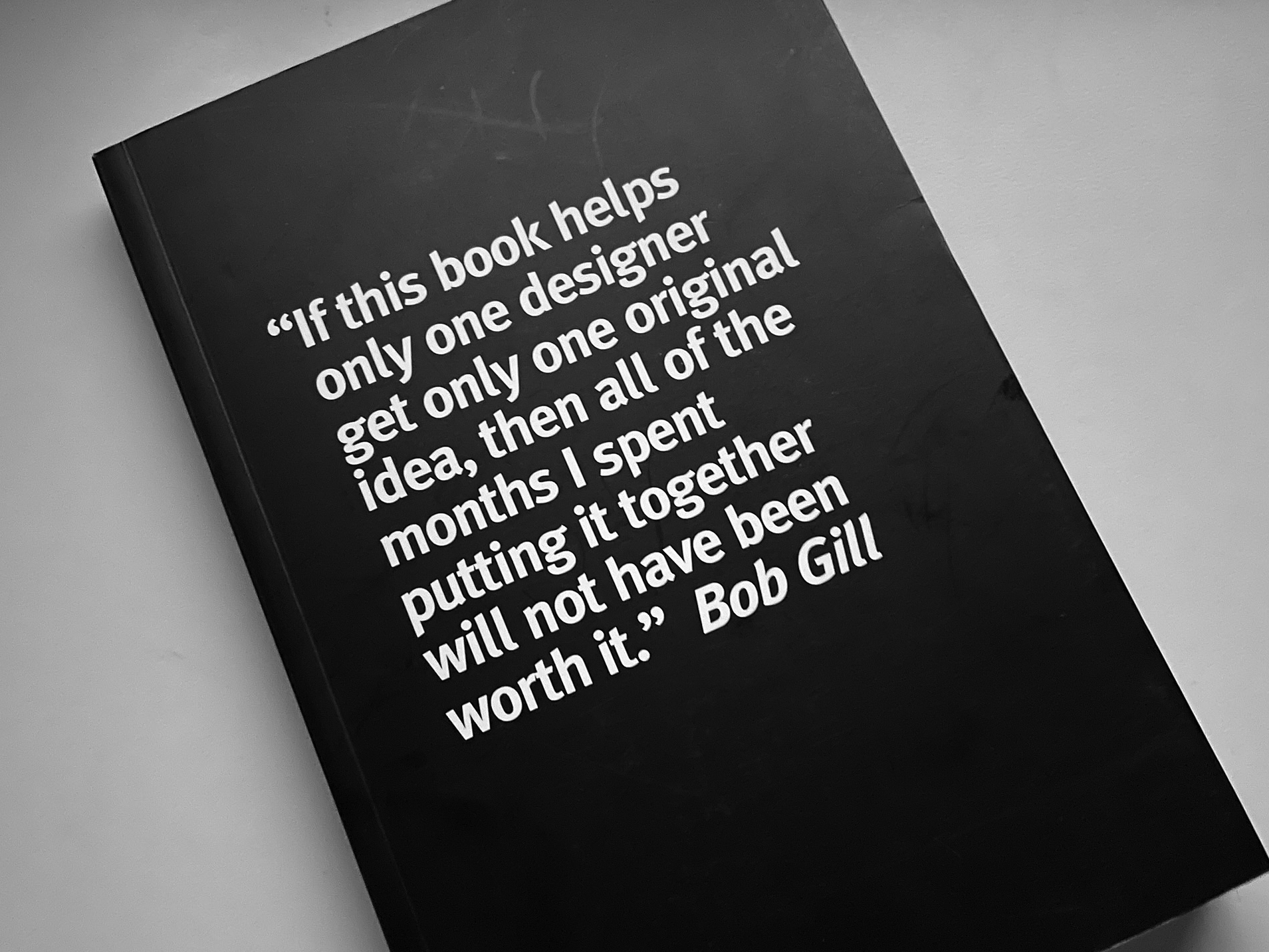

The cover of Unspecial Effects carries Bob’s thought that “If this book helps only one designer get only one original idea, then all of the months I spent putting it together will not have been worth it”.

Having taught and influenced countless thousands, Bob can rest knowing the effort was more than worth it.