Posted on 28 September 2022 by Jeff Fuge | Reading time 4 mins

Buzz in if you know the answer… or you think you know the answer… or you have the answer to a question you think I should have asked. ‘Buzzing in’ has become an increasingly annoying phenomenon we are all having to suffer and navigate around.

Correctly answer a starter question on the BBC’s University Challenge and you bag your team 10 points plus the chance to answer three more questions, each worth 5 points.

However, buzzing in before host Jeremy Paxman has finished reading the question can be a costly business. Interrup with the wrong answer and your quizzing cock-up loses your team 5 points and allows the other team chance to hear the question in full.

Buzz in when you hear “Who was the first wife of King Henry VIII…” then smugly answer “Catherine of Aragon”, and you look a fool when the full question turns out to be “Who was the first wife of King Henry VIII to be beheaded”. (It was Anne Boleyn.)

Buzzing in is therefore balance of risk versus reward: you could end up with a 25-point gain, but you risk a net 30 point loss. And if your impetuous answer is way wide of the mark, you also the risk the ire, disdain and incredulous stare of Paxman.

This makes even the keenest minds and itchiest buzzer fingers think twice about leaping in when only part of the question is known.

But away from this televised battle of the brains, ‘buzzing in’ has become an increasingly annoying phenomenon – and one that seems free of risk when the answer is wrong.

Professional platforms, amateur answers

Undertake a search online with the likes of Google or Bing – or look for a product on Amazon or eBay – and ahead of the carefully evaluated algorithm-driven answers given by these platforms, advertisers now buzz in with their own less-informed guesses.

Google, Amazon and the rest can base their answers on a depth and breadth of data that advertisers on these platforms cannot. Advertisers are often buzzing in chiefly due to the presence of certain keywords in your search. If it contains a certain term or combination of words, they assume their ad contains the answer you are looking for.

Calling these ads ‘guesses’ is perhaps too generous, as far too often they are absurdly wide of the mark. Paxman would be peering over the top of his glasses, tutting and scornfully saying “Noooooo!” in a way that would make the offending contestant shrivel.

Worse still, this new form of buzzing in places advertisers’ answers in the top spots of any results listing. Here, they assume some kind of heightened relevance and accuracy as Google and others have habituated us to expecting the first results to be the ones that answer our search most accurately.

Worse still, some advertisers’ guesses do not even answer your question but their own.

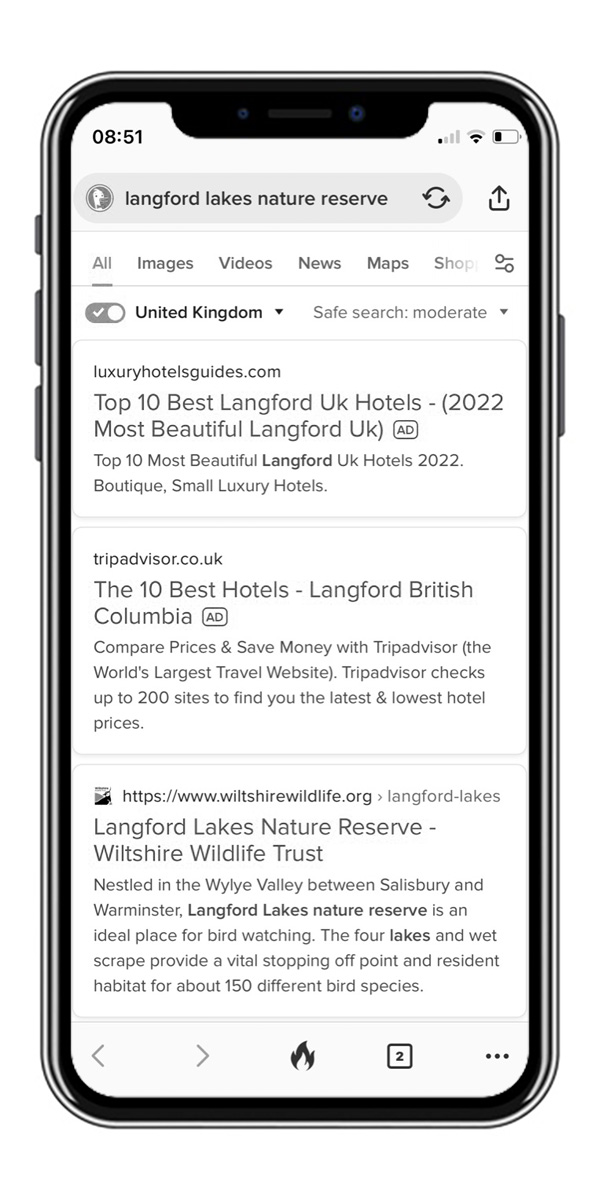

Here’s an example. I recently needed details of a local nature reserve and keyed the name into Bing.

The search engine’s own guess is pretty well informed. They know where I am and what is around and about, so can marry my search up with the fact that Langford Lakes nature reserve is just down the road.

But two ads topped the list in the search results, shunting Bing’s useful answer down the screen. The first was for a luxury hotels website promising ‘beautiful hotels in Langford’.

Despite its name, the nature reserve is not somewhere called Langford and there are no hotels nearby. Langford is, in fact, around 50 miles away in the next county. (And, according to the very website that placed the advert, it turns out Langford has only one hotel, not lots of beautiful ones!)

The second ad wanted me to travel even further as it was promoting hotels in Langford, Canada.

Nothing about my search indicated any interest in hotels, but the advertisers buzzing in decided that’s what I should have been asking about.

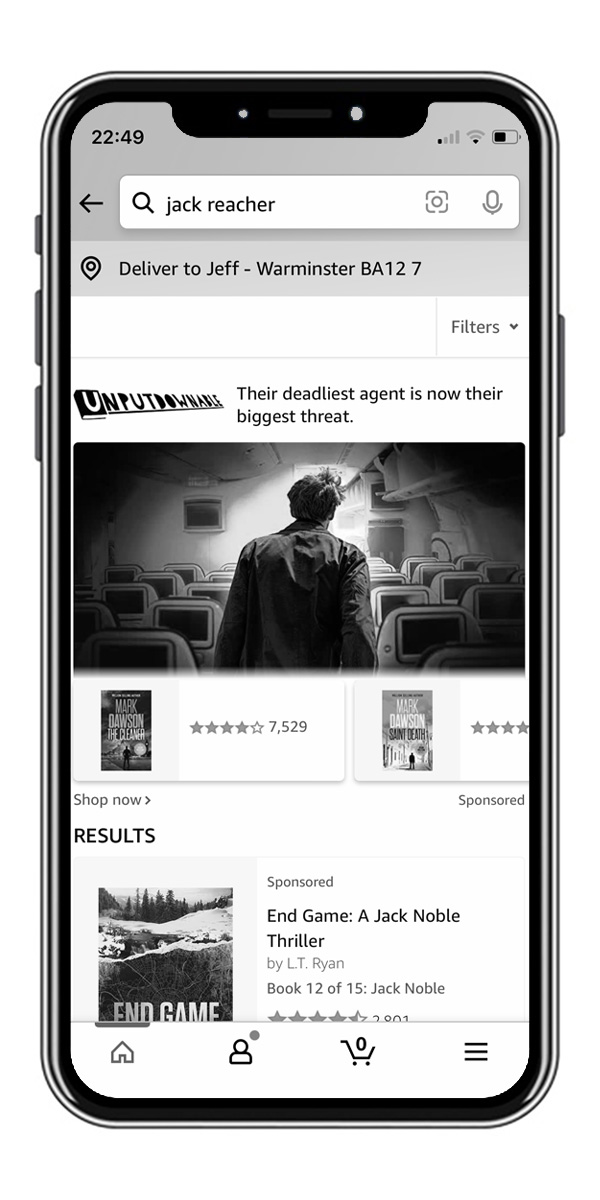

A recent search on Amazon for author Lee Child’s famous fictional hero Jack Reacher yielded similar results.

To find what I was looking for, I had to scroll past promos for books that were clearly not about Jack Reacher and clearly not by Lee Child. In this instance, the ads filled the screen and there was nothing pertinent to my search above the fold.

If the 6′5″, 18-stone Reacher met with folk intent on answering his questions so unhelpfully, they would be likely to end up in the emergency room!

All gain, no pain?

Buzzing in on University Challenge could gain you lots but cost you more. Conversely, buzzing in with an advert seems to only offer upsides.

Advertisers and platform owners both win if you click an ad, but there is no immediate cost to either if you don’t. So the most inane, annoying and intrusive of wrong answers to your searches can be made without jeopardy.

On the face of it, the all-upside-no-downside appearance of pay-per-click advertising makes it seem hugely compelling both to platforms and advertisers.

But it’s not quite right to say there is no cost to buzzing in with irrelevant answers. There is – but it’s subtle and it’s not immediate.

If you’re an advertiser with poorly targeted pay-per-click ads, you’re harming your brand. And if you’re a platform that has become beguiled by what PPC is doing for your bottom line (and reluctant to introduce rules or filters around relevancy) you’re doing so at a long-term cost to your brand too.

In each instance, making money by frequently pissing off your audience is not the way to get you through to the next round.

Buzzing in should buzz off!

In 2002, Jeff Bezos famously stated his desire for Amazon to be “Earth’s most customer-centric company”. Amazon has done much to deliver on that mission, but the introduction of adverts in search results feels like a step backwards.

There are now two customers that it is trying to serve at the same time – you and the advertiser. While the interests of the two are sometimes aligned, too often they are definitely not.

In terms of long-term trust and affection, Google, Bing, Amazon, eBay and the rest are all losing points by allowing buzzing in with duff and annoying answers.

While focussed on ad revenue (which was over $30 billion at Amazon in 2021) rather user delight, they are creating cracks into which more customer-focussed brands could drive a wedge.

Maybe their team captains should unwire those buzzers – or at least keep the fingers of the more over-eager, ill-informed and self-serving advertisers well away.